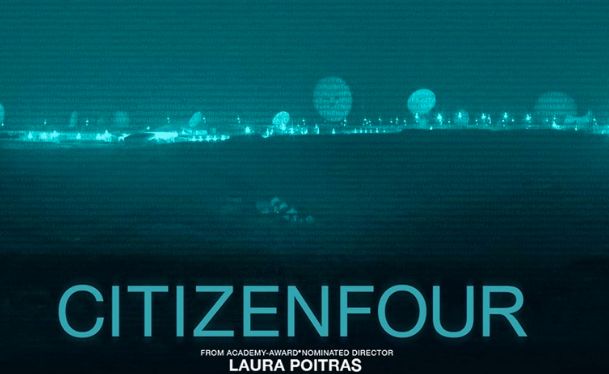

Citizenfour

There is a scene in Citizenfour where Edward Snowden is running gel-smothered fingers through his hair in a Hong Kong hotel room. The camera is fixed on him, but the only sound is coming from England – the blare of the BBC reporting on the massive story Snowden has just uncovered. An extremely English-sounding Englishman is talking about how the whole escapade sounds like a John Le Carré novel. And he’s right. But not only that, Citizenfour plays out like a film adaptation of a John Le Carré novel – equal measures of unbelievability, outlandishness, intrigue and overwhelming excitement.

There is a scene in Citizenfour where Edward Snowden is running gel-smothered fingers through his hair in a Hong Kong hotel room. The camera is fixed on him, but the only sound is coming from England – the blare of the BBC reporting on the massive story Snowden has just uncovered. An extremely English-sounding Englishman is talking about how the whole escapade sounds like a John Le Carré novel. And he’s right. But not only that, Citizenfour plays out like a film adaptation of a John Le Carré novel – equal measures of unbelievability, outlandishness, intrigue and overwhelming excitement.

Citizenfour, the HBO documentary by Laura Poitras, starts off before the revelations. We see Glenn Greenwald at home in Brazil, surrounded by dogs; we hear conversations between unknown people and we read text from what looks like the screen of a 1980s computer – promising a story that is going to shake the foundations of the surveillance state. All the while, days, dates, places, etc are appearing at the bottom of the screen, feeling more Bourne than La Carré.

Eventually we find our way to a hotel room in Hong Kong. Snowden is there along with Glen Greenwald and his Guardian colleague, Ewen MacAskill. It’s striking how articulate and calm Snowden is. He chooses his words carefully and never seems flustered by the attention of the journalistic heavyweights that surround him. He can even understand MacAskill’s accent, which as a fellow Scot, I have to give Snowden great credence. The only time Snowden seems anything but measured is when he considers the family and friends he has left behind. He shakes his head in disbelief and disgust when he hears what his girlfriend has to say. He maintains that he be the only one nailed to the cross for his actions. MacAskill seems to want to get to the bottom of his apparent selflessness. It’s debatable that he ever does.

Poitras is playful with her filming technique. In the scenes with Snowden she appears to act as a surveillance camera, remaining silent for the most part and insuring that we see Snowden in as natural a way as possible. We see him gel his hair, as mentioned above; we see him type emails; we see him watch reports of himself on the television; she holds an uncomfortably long shot of him looking out the window as he considers the news he has just learnt from his partner. It’s almost as if the filmmaker is trying to get us to understand just how uncomfortable surveillance is. In a later scene, we see Snowden and his girlfriend in their Moscow apartment. But we are not in there with them. The camera is fixed outside and we are viewing them through the window in to their kitchen. It feels intrusive.

Poitras doesn’t attempt to make a hero out of Snowden or Greenwald or anyone else concerned with the revelations, instead she lets the camera roll and moves it appropriately, letting the viewer survey the hours and days that pass. We feel like we are part of the décor of the hotel room; we are a wallflower. Her skill as a documentary maker is that she allows the story to tell itself. The film’s skill as a documentary is that the story is as cinematic as one penned by a Hollywood screenwriter.

Find more of our content at www.podestrians.net.

We produce a weekly filmcast. Subscribe on iTunes at https://itunes.apple.com/gb/podcast/podestrians-podcast/id920231768?mt=2