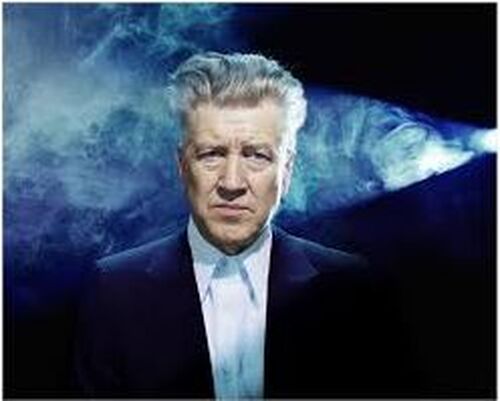

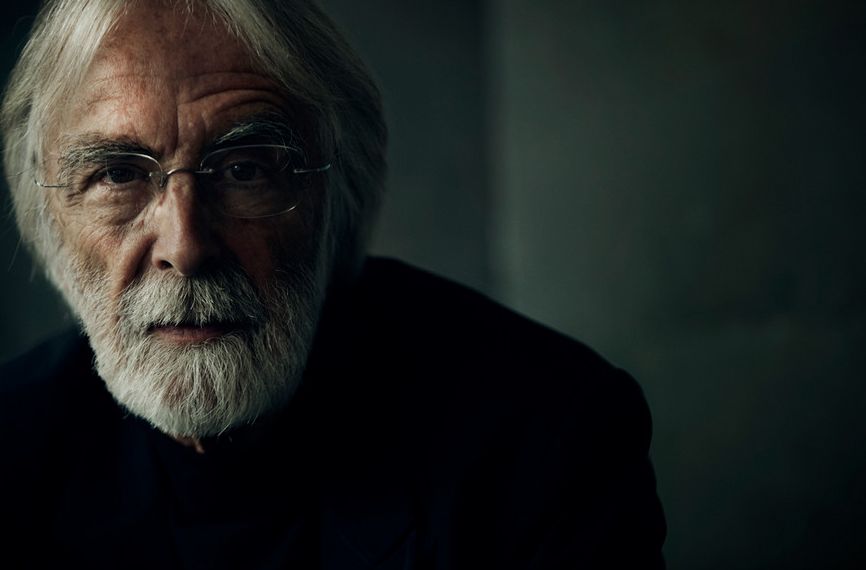

Exploring Michael Haneke: Amour

With an incredible opening that calls to mind the closing shot of Cache, Michael Haneke begins his 2012 film, Amour by placing his camera on an audience as they prepare then start to listen to a piano concert. Showing the crowd as they settle into their seats then watch the performance, Haneke allows his subjects to blend into the crowd without calling attention to them. Masterfully, we are shown everyone without focusing on anyone. This beautiful humanist opening seems to communicate to the audience that we all live our existences, yet, experience the world among a collection of people that are also living individual lives. A brilliant bit of foreshadowing to his most overtly humanist film, Michael Haneke also informs the audience from the opening shot that the movie we are watching is one focused on the act of observation. Not only do we begin the journey by observing, we then continue observing our subjects, observing their life, age, and union.

With an incredible opening that calls to mind the closing shot of Cache, Michael Haneke begins his 2012 film, Amour by placing his camera on an audience as they prepare then start to listen to a piano concert. Showing the crowd as they settle into their seats then watch the performance, Haneke allows his subjects to blend into the crowd without calling attention to them. Masterfully, we are shown everyone without focusing on anyone. This beautiful humanist opening seems to communicate to the audience that we all live our existences, yet, experience the world among a collection of people that are also living individual lives. A brilliant bit of foreshadowing to his most overtly humanist film, Michael Haneke also informs the audience from the opening shot that the movie we are watching is one focused on the act of observation. Not only do we begin the journey by observing, we then continue observing our subjects, observing their life, age, and union.

Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) and Anne, (Emmanuelle Riva) a pair of retired music teachers have enjoyed their long lives together living blissfully for themselves. Their daughter Eva, (Isabelle Huppert) enjoys success as a musician, traveling through Europe while on tour leaving the couple to enjoy the life they have built together. However, an intrusion into their cultivated lives interrupts their well-manicured existences. On the evening of the concert, they arrive home to find their front lock disrupted as it appears someone attempted to break-in. The two take the incident in stride vowing to call someone the next day to fix the lock. The audience watches the couple change their clothes, put their shoes and coats away, and commence their nightly bedtime routine. Likewise the next morning, Anne prepares breakfast as she always does, Georges remarks that the salt shaker is empty before refilling it, and the morning commences, as mundane as any other. That average day comes to a crashing halt when Anne freezes in what she is doing at the table and Georges in unable to get her attention. We soon find out that Anne has suffered a stroke, and just as an unknown intruder interrupted their lives the previous evening, so has another black cloud encroached upon their lives. This unwelcome guest in the form of a stroke takes its toll on Anne as the audience watches her begin a steep decline physically and mentally. Georges shifts his role from partner to caretaker, resolved to keep his wife's wishes to remain in her home. Preserving his wife's dignity in this way also means Georges must lose himself in the helpless observation of being unable to help Anne recover, only able to keep her comfortable through her decline. The close observation Georges experiences of watching Anne's decline reminds the audience that the inevitability of death spares none of us. The film also dispels the notion that there is any death that comes easy. We fool ourselves into believing that the older we are, the more we are accepting of death we become, and as the deterioration of our bodies progresses, accept the end of our lives more so than in our youth. That, of course, may be true for some, but on the whole human beings avoid accepting their mortality at all costs. The idea that it is easier to accept the death of an older person because we can comfort ourselves and say things like "they lived a full life" is a misconception. Georges shows a decline, just as Anne does, but his is from dealing with the heartache and despair of watching his lifelong partner succumb leaving him with an inevitable void. There is no sense of ease in Georges' preparation of the loneliness he will endure in a life without Anne, simply because she's in her 80's. Georges still loves her, and is completely devoted to the life the pair has created. Often in end-of-life care, we neglect the fact that the person responsible for the caretaking is also losing someone and facing the reality of preparing for a life alone. In the most subtle ways, Haneke shows the weariness grow on Georges' face the longer he cares for his dying wife. Still, though, Georges' commitment to his wife's wishes and desire to fulfill them illustrates to the audience that the bonds we form through our relationships make life worth living. Just as Ingmar Bergman is often cited as being too world-weary and bleak, so too is Michael Haneke. Amour stands as proof that Michael Haneke makes his films from a deeply humanist place and cares profoundly for both the characters he creates and the audience that watches his films.

The future and one's mortality has an interesting relationship with the past. Amour does a brilliant job of expressing how comforting it is to reminisce about the past when the future looks bleak or uncertain. As the stroke occurred, Georges was sharing with Anne a story from his past that she had never heard before. The tale Georges shared was one that reminds the audience that observation is the cornerstone of the film, as the story he shares recalls the emotional response he had to seeing a particular film in his youth. Each time that Anne shows a new decline in her health, Georges comforts her with a story about his past. Rather than recounting stories about their marriage, Georges recalls memories of his youth, driving home the point that he is uncertain and uncomfortable with his future and is also finding solace in returning to thoughts of the past. When Georges tells his daughter Eva about her mother's health woes, she immediately recalls a memory from the past, and remarks that it brought her comfort. Repeatedly returning to the past proves a comfort to Georges, Anne, and their family exploring the link between mortality and the past in an interesting way.

I've spent many months marveling at the directorial mastery of Michael Haneke, and I was just as impressed as I have been through this entire project through my viewing of Amour. I am enchanted by the way Haneke revels in the day-to-day life of his subjects, both making them more relatable to the audience and driving home the impression that life is made up of mostly everyday activities that rather than the significant events we often reminisce upon. In Amour, this attention to the small aspects of the day makes the impact of Anne's stroke even more potent as the disruption to their lives is made even more apparent. An element of Michael Haneke's films that I find most absorbing is his limited use of a score. Haneke doesn't rely on music to charge his audience's feelings; instead, he abandons all emotional manipulation, solely using the story for narrative impact. The casting in Amour was brilliant giving the pedigree of the two leads. Jean-Louis Trintignant has been in a number of films that rank among the best, including acting as the male lead in my mon bébé's (François Truffaut) final film Confidentially Yours. Likewise, Emmanuelle Riva has a full resume which includes a starring role in the seminal Alain Resnais film, Hiroshima Mon Amour. Taking such notable actors who have filmed evidence from their prime and placing them in a film about aging, Haneke furthers the reality that aging is universal and even people as radiant as classic actors cannot avoid the cost of aging. Calling to mind the backgrounds of two of the finest French actors of their time was a brilliant addition to the reality of aging in Michael Haneke's Amour. Much like his 2009 film, The White Ribbon, Michael Haneke creates a Tarkovsky inspired film in Amour. Much of Haneke's framing and shots are reminiscent of the extraordinary Soviet filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky throughout his entire filmography, but especially so in both of his Palme d'Or winners. Such clear Tarkovsky inspiration works well for both of these films due to their somber look at human malevolence in The White Ribbon, and mortality in Amour. The ways in which Haneke can communicate the themes of his films through such subtle cinematic language is why he stands at the top of the list among the best working directors.

Amour represents a departure from the type of film I've grown to expect from Michael Haneke; it is overtly sentimental, touching and heartwarming, and effortlessly beautiful. Haneke completely disappears, creating almost a documentarian view on end-of-life care and commentary on aging. As someone who has immersed myself in his films, I find all of Haneke's filmography incredibly Humanistic, though, to the average viewer or someone new to Haneke, his humanism is most evident in Amour. The collective conscience Haneke brings to life in the film acts as a stunning reminder that each of us shares our experience in the world with each other, and no matter how upsetting it is to consider, we all will meet the same fate at the end of our lives. Michael Haneke also honors his subjects, revealing that growing old with another person isn't the horror it's made out to be. If only each of us could be so lucky to find a Georges or an Anne to traverse our lives with; someone who could remain so devoted to our wishes even at the most trying times and do anything in their power to stay with us until the end. Beautiful, heartwrenching, and captivating, Amour disproves the notion that Michael Haneke is a cold, emotionless filmmaker.