Exploring Michael Haneke: The White Ribbon

The first of Michael Haneke's two Cannes Palme d'Or awards was for his 2009 film, The White Ribbon.

The first of Michael Haneke's two Cannes Palme d'Or awards was for his 2009 film, The White Ribbon.

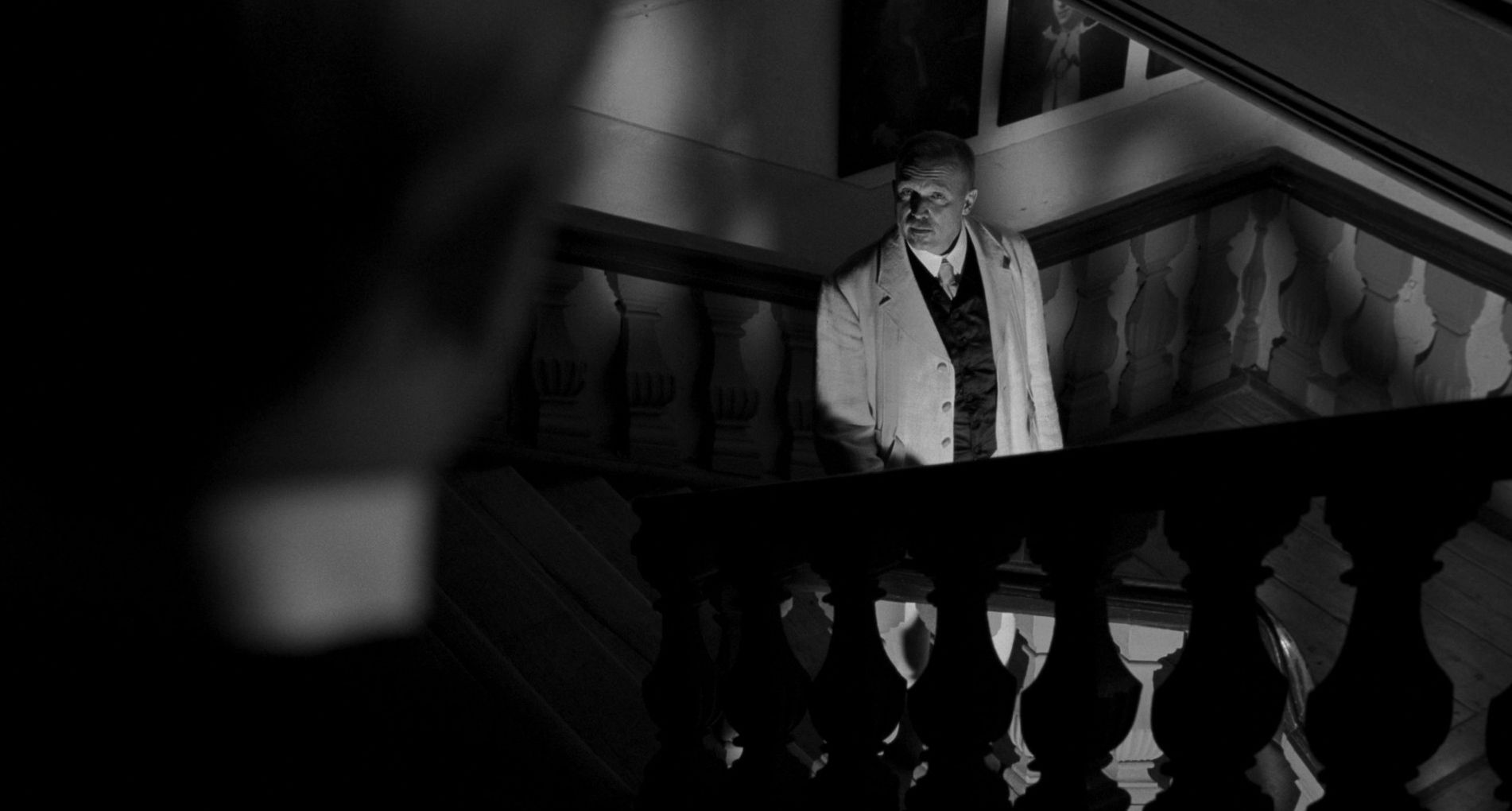

Haneke's two and a half hour black and white German film with no musical score may seem like an odd entry point to such critical acclaim, but The White Ribbon offers a probing commentary of authoritarian regimes, questions the idea of origination of malevolence, and examines the relationships between stifled parents and their children in a way only Michael Haneke can. Haneke delves beneath the facade of cordiality in a German village just before WWI. When a series of evil deeds begin to occur, the town is forced into suspicion of one another while trying to secure the uniformity enjoyed in the town. Haneke reveals, as he removes layers throughout the film, that these behaviors and occurrences don't exclusively belong to a foregone era. In the time since WWI, evil still happens and oftentimes we can not discern its origins nor is there always a clear indication that such evil exists beneath such a formal cordial society. A silent opening and credit sequence sets the tone for what is to come, a startling raw depiction of real life beneath the surface level human interactions. Forever interested in human behavior and the idiosyncrasies of emotion, Haneke tells the story of the events that took place in this village through the narration of a teacher in the town who admits that his recollection may or may not be completely factual. Delving beyond the veneer of society to bring broad philosophical concepts to daily human existence is a strength of Haneke's and one expertly exacted in The White Ribbon.

Patriarchal authoritarian society governs the village under Michael Haneke's microscope in The White Ribbon and finds itself challenged by the outbreak of violence rather than troubled by it. When a trip line is affixed between two trees for a doctor's horse to fall over, and a woman plunges to her death in a workplace accident, and a local baron's son is hung upside down and abused in a mill, the town seeks to find out who is behind the deeds in order to punish them and restore order rather than seek reparations to those wronged. It becomes clear that in this society, laws being broken and routines being disrupted only suggests a threat to the system rather than a threat to the individual. Evil when exacted against human beings is a threat the the human condition everywhere as opposed to the ruling system, but those who benefit from such an authoritarian structure will do anything to keep it in place. Those in the village that do benefit are the same people that humiliate and silence the women in their lives and beat and molest their children when the veil of formality is lifted. Everyone in this town is referred to by their occupation, or rather, their place within this ruling structure, refer to each other using English honorifics and behave well in public to conceal their own evil deeds. Maybe to conceal their own heinous tendencies, or simply as a means to keep the "disruptions" temporary, the authoritarianism in Haneke's German village only grows in response to the villainous deeds taking place.

It puts human beings at rest to think that malevolence has an origin that can be traced. If we can pinpoint the genesis of evil to a morality or ethical structure, we'll know what to do to avoid its wrath. Michael Haneke's The White Ribbon, suggests that the nature of human beings, like the ones depicted in the film, bring about the risk of immorality. If the human condition itself is to blame for wickedness then Haneke asserts that perhaps bad things happen simply because they do. Similar to all of Haneke's films, the assertion that evil has no single origin is an unsettling claim designed to instill discomfort in his audience. This discomfort stems from the self-reflection Haneke encourages through his art. When an audience can see the possibility of villainous behavior manifesting itself in them, the belief that we are better than we are is shattered. What is especially disconcerting about the violence depicted in The White Ribbon, is that despite the film's setting of 1914, the acts are not cemented in the past. We as human beings have not overcome molestation or fighting one another, and will likely hear about such events happening in our own time on any edition of the nightly news. The fact that there was no clear perpetrator in The White Ribbon suggests that Haneke seeks to illustrate that no one, in particular, being responsible for evil means that anyone is capable of malevolence.

The relationships between adults and children in The White Ribbon is startling. The inherent violence or neglect at the foundation of each of the children with their parents is the heartbreaking reality of such patriarchal authoritarianism. In this society, children are disruptions and in the way unless they are being perfectly mindful of their fathers. Children are seen as a reflection of their fathers under such strict authoritarianism and are therefore only an asset if their behavior is pure. It would seem impossible for their behavior to be pure as they grow up around such deep-seeded disdain. In their homes, fathers molest their daughters, beat their children and silence women despite their demands that their children wear visible signs of purity. This upbringing seems destined to bring forward the next generation of patriarchal authoritarian monsters. Are the children simply acting what they see, or is there more to Haneke's story. Thinking back to Benny's Video, Funny Games, and Cache, it is clear that Michael Haneke does not think of children as angelic creatures that come engrained with a sense of innocence. Rather, it is the children in Michael Haneke's world that have not matured to accept the cordial formalities of life within a society that act out motiveless experimental vengeance revealing the potential in us all to turn to evil. Just as in every other question posed in the film, Michael Haneke is not interested in giving us an answer to how violence in children manifests, but instead, begs that we look into our own beings to uncover the real possibility that the penchant towards violence exists within each of us.

Michael Haneke has a knack for bringing expansive philosophical concepts and metaphysical concerns to an audience by incorporating them into the day-to-day life of the characters in his films. By showing minute activities and seemingly insignificant aspects of life, Haneke is able to paint a whole picture of all that makes up a life. He shows how much the trivial aspects that make up most of our existence inform our life as a whole. Haneke's ability to make real the conceptual aspects of philosophical study proves that he's working on a level that few can maintain. His quiet yet deliberate filmmaking, his careful blocking of scenes, and his masterful use of sound undoes all film training that movies are a puzzle to be solved, but rather, an event to be experienced. The best filmmakers move their audience with their work and leave them impacted for long after the credits roll. Haneke knows there is truth about the world that can be discovered uniquely through cinema. He wants to leave the audience with questions and provide plenty of opportunities to think, this is the precise reason Haneke subverts the mystery in his film. We may enter The White Ribbon thinking we are being presented with clues and will ourselves be able to solve the mystery in the film before we slowly realize there is nothing to be solved, but rather, concepts to be considered. It's never easy with Haneke, and it's never comfortable. One of the ways the filmmaker consistently proffers a sense of discomfort is through his critique on voyeurism. Haneke holds a scene longer than many filmmakers, and to great effect, allowing his audience to never be devoid of the reality that we are watching a film. Knowing that we are watching what is often hidden shakes our tendencies to leave such moments private and turns the camera on ourselves and forces us to decide how we feel about seeing such intimate moments. In each of his films there exists an element of interaction with a camera or screens, and like Hitchcock, Haneke seems to assert that human beings enjoy voyeurism at least to some degree. His endless pursuit to infuse his films with postmodern philosophy while presenting uncomfortable ideas such as a possible penchant for children to be evil or the origin of malevolence cements Michael Haneke's place among the most brilliant of auteurs and a true gift to cinema.