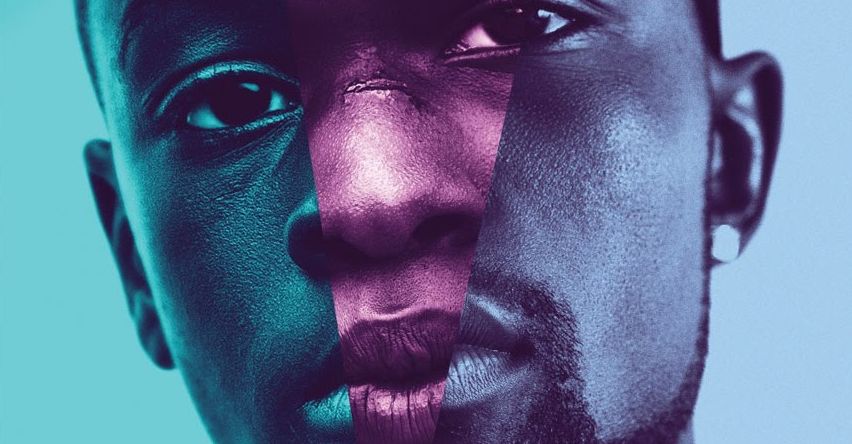

Moonlight Humanizes the Struggle to be Loved and Accepted

Tarell Alvin McCraney’s play “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue” touches on the universal longing to be loved, accepted, and supported. Black youth and the LGBTQ youth community need it now more than ever.

Tarell Alvin McCraney’s play “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue” touches on the universal longing to be loved, accepted, and supported. Black youth and the LGBTQ youth community need it now more than ever.

[The following article originally appeared on shrinktank.com]

Moonlight’s historic win for Best Picture comes at a pivotal time in our culture. On the one hand, the national conversation has never been more open regarding the struggles of the LBGTQ community. On the other hand, laws like North Carolina’s HB2 and the unsuccessful attempts to reverse the law continue to remind Americans that not all folks are as open to humanizing the LGBTQ community.

Moonlight, Barry Jenkin’s film adapted from Tarell Alvin McCraney’s play “In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue” confronts the uncomfortable fact of homophobia rooted in black American culture. McCraney and Jenkins are quick to insist that Moonlight wasn’t a reflection of every black gay man’s plight, but the film is a platform to showcase the universal commonality of the human experience and the longing for unconditional acceptance.

Moonlight is McCraney’s life on screen.

Early on, McCraney showed potential in the world of theatre. He was even taken under the wing of August Wilson, the Pulitzer Prize winning black playwright who this past year was a recipient of a posthumous Oscar nomination for the adapted screenplay of his play Fences (the category that MCraney won his award for). McCraney attended college at DePaul University and then headed off to France where he connected with Peter Brook’s Bouffes du Nord theatre. But in the summer of 2003, the news of his mother’s death brought McCraney back to his old life and the childhood he continues to struggle to leave behind. “I was trying to figure out what little me and middle me and grown me were doing that was the same and not the same,” he said about the play’s structure and inspiration. “What patterns I was repeating, what is this life?”

His mother’s death from AIDs-related health problems after two years of dementia and her death brought back strong emotions of loss and grief, but especially panic. “The panic came from there being a whole other part of me that wasn’t being accessed in the work I was doing,” McCraney has said in interviews. He revisited his mother’s decline into crack cocaine addiction. McCraney’s mother went into rehab when he was 13. McCraney states, “I don’t know if I’ll ever be done trying to suss out the trauma of growing up with an addictive parent. I don’t know if that will ever go away but I wish like hell that it would.”

The trauma of his mother’s addiction and absence of his own father is contrasted with Blue. Blue was the first man in Tarell Alvin’s life who looked out for him, cared for him, and the first man that McCraney looked up to. Blue taught him how to ride a bicycle. He took Tarell Alvin to the ocean and held him as he learned to swim. Blue was also a drug dealer, but that didn’t discount the grace and compassion that McCraney felt from Blue and continues to feel for Blue. In the film Moonlight, Blue is depicted in the character Juan, played sublimely by Mahershala Ali in an Oscar-winning performance.

Finally, McCraney’s original text explored the traumatic bullying and struggle to connect he experienced for being different. He was bullied almost daily as a young child, bullied for being silent, for not being into sports. McCraney was called “faggot” before he knew what that word meant. He would be beaten – he was hit with bricks and lost several teeth. Tarell Alvin also wrote of the solitary sexual encounter he experienced with his only true childhood friend. The experience turned quickly into a cruel betrayal by the first boy he loved, who sided with the bullies. The 60-odd typed page script was quickly finished. McCraney titled it: “In Moonlight, Black Boys Look Blue” to capture the anguish and attempts to escape the anguish that the script explored. “It’s probably under the moonlight that we see that black boys can be blue, can be sad and sullen and intimate,” he said. “It’s under starlight that we see them differently, or that we get the chance to.”

Similar Childhoods Brings Moonlight From Page to Screen

Once he finished “In Moonlight…”, McCraney was unsure what to do with the script. He didn’t write it in a traditional play format and to him, it felt more like a film than a play. But at the time he had no clue how to get films made, so he stashed it away and continued to build on his impressive theatre career.

It would be roughly ten years before director Barry Jenkins would get his hands on the script “In Moonlight…” from a small film-making collective in Miami called Borscht. McCraney had done some work with Borscht and with his permission, Borscht sent the decade-old script to Jenkins, who had a background that was uncannily similar to McCraney’s own upbringing. Both men had grown up in Liberty City. Jenkins attended the same elementary and middle schools, although they did not know each other and Jenkins was a grade above McCraney. Jenkin’s single mother was also an addict. Where McCraney’s escape outlet had been theatre, for Jenkins, it was sports. He played football at Florida State University and also enrolled in the film program. When Jenkins read the script he saw much of his own life in the text and asked McCraney if he could write and shape it into a film.

McCraney is appreciative of all the praise for the film but for Tarell Alvin McCraney, watching “Moonlight” isn’t the wonderfully transformative experience it is for many other people. It’s emotional. It’s painful. It’s struggle, embodied. “It’s a palpable snapshot of memories and dreams that is difficult to sit through,” he said. “The first time I saw it, I went through a pretty bad depression. The second time, I burst into tears midway through. It’s hard. It’s rough.” In an interview with The Guardian McCraney further described the impact of watching his life on screen. “I did remember feeling very depressed and very heartbroken about a lot of it. Mostly because these are not things that I have found the answers to and understand how they work. I actually ended up feeling that these are still looming questions in my life, questions about my own identity and my own self-worth that I’m still trying to figure out. Then seeing the film again, I was like shit, these are still here and they’re not going anywhere.”

Alarming Trends for Black Youth and the LGBTQ Youth Community

The success and attention that has been shown Moonlight will hopefully bring to the national spotlight some of the more troubling statistics surrounding the themes and storylines showcased in the film. A study published last yearshowed suicide rates among black boys ages 5 to 11 have doubled in the past two decades, while rates among white boys of the same age decreased. Although black Americans make up about 13.3% of the population, among the younger children, 36.8% of suicide deaths involved a black child.

Suicide is the leading cause of death for gay and lesbian youth in the United States. The rate of suicide attempts is four times greater for LGBTQ youth. Thirty percent of gay youth have attempted suicide near the age of fifteen, and almost half of the Gay and Lesbian teens state they have attempted suicide more than once. Victimization and family support also play a significant role in suicide rates. LGBTQ youth who come from a highly rejecting family are over eight times more likely to attempt suicide as their LGBTQ peers who report low-to-no level of family rejection. And finally, research suggests that for everyepisode of victimization that LGBTQ youth suffer, such as physical or verbal harassment or abuse, the likelihood of self-harming behavior increases over twofold.

McCraney says of the film’s impact and relevance, “you know, some people say to me ‘Moonlight is so great, it is going to change things’, and I think it is maybe helping a few people to find answers to some things. But the attitudes and problems it portrays are not historic ones, they are here and now.” Moonlight humanizes the struggles of gay black youth. Hopefully, McCraney’s coming-of-age story can be a beacon of hope, understanding, and empathy for black youth and the LGBTQ youth community.

Check out more articles written by Jonathan Hetterly at shrinktank.com