Ousmane Sembene’s Emitai

How about some Senegalese spice - Ousmane Sembene’s 1971 film, Emitai, is fueled by a spirit of protest that resonates decades on. The fact it wasn’t released in Sembene’s home country of Senegal and censored in other francophone countries endorses the strength of its message in a time when colonialism was something more tangible than chapters in textbooks.

How about some Senegalese spice - Ousmane Sembene’s 1971 film, Emitai, is fueled by a spirit of protest that resonates decades on. The fact it wasn’t released in Sembene’s home country of Senegal and censored in other francophone countries endorses the strength of its message in a time when colonialism was something more tangible than chapters in textbooks.

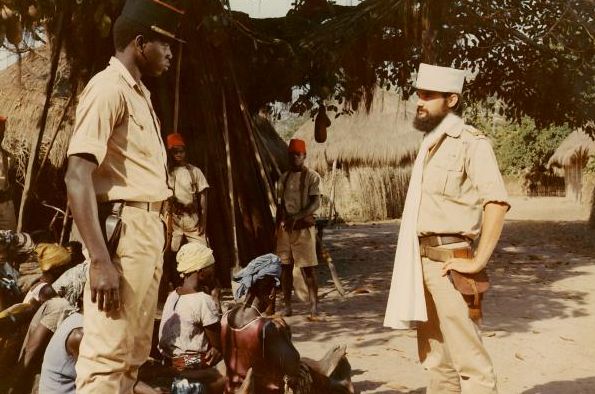

The film narrows in on the Diola of Senegal. The Second World War is well underway and the French colonial government is raiding villages for young men to fight the Axis powers. We see soldiers, Senegal indigenes commanded a white Frenchman, round up men in a particular Diola village with relative aggression and then thank them for volunteering as recruits. Fast forward a year later and we have the women, and what remains of the young males, tilling the water-logged terrain for the cultivation of rice.

The mundane rice cereal will come to serve as the conduit of the primary conflict. The young men plucked for war are not enough. The colonial government is set to return with a demand for the rice to feed their army. It is at this point Sembene gets to prod at the layer of religion. This community could stand having their sons and brothers taken away to fight in the white man’s war. But the rice is a no go. It is not for physical but spiritual sustenance. The rice is to be reserved for the gods. You could argue that the French didn’t need the rice either. They play a game of oppression.

This Diola village hides the rice and the men, led by their elders, contemplate confronting the soldiers. The elders are based in a hidden shrine awaiting counsel from the gods on the course of action to take. The soldiers present a grave threat, but crossing the gods is another matter. The anger of the gods is to be feared more than the undue oppression they face. Sembene’s camera has us very involved in this meeting compelling the audience to have a vote on the matter.

To one of the elders, Djimenko, the silence of the gods is deafening and he decides to confront the soldiers is the way to go as opposed to sitting and making sacrifices, which Sembene presents as a futile act. I sided with Djimenko. I reckon most people of our time will too. He leads some men, armed with rudimentary weapons like spears and bows and arrows against the soldiers’ rifles without the protection of the gods. Naturally, it does not go well for Djimenko and his men who fling their spears well short of the advancing soldiers. They are forced to flee and the elder himself is carried off from the clash wounded.

The soldiers proceed to the village where rice is obviously hidden so they torture the women who have remained by having them sit in the scorching sun. The women will only be released when the rice is turned over. The soldiers occupying the village evoked Fela Kuti’s gripes in Zombie in the way they were presented as mindless drones - "no break, no job, no sense". They are ordered around by two French officers who just sit in the shade watching on as the soldiers also find themselves guarding the women in the same intense heat meant to be used as an instrument of torture.

Then there’s the French politics at play as General Charles de Gaulle, a name I hold synonymous with the French resistance of the Nazis becomes the leader of France as WWII winds down. He takes over from France’s Vichy government headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain in a momentous moment the French. But the soldiers, like the zombies they are, are lost in a purgatory of unconsciousness. They only argue over the ludicrousness of having a mere two-starred General like de Gaulle taking over from the seven-starred Marshal Petain as they replace posters of the latter with the former. Sembene has no love for the French colonists, but you a sense some disappointment from him in the natives under their command.

Our director remains interested in the Diola village and maybe, as events unfold in France, this community can feel the vibe of change and resistance and they become even more resolute, the women especially, as the rice is described as the woman's sweat - sanctified by the gods. Sembene has too much affinity for this village to have them just sit by. He is fully aware of the reality and poor odds, but content to set this protesting community on the path of tragedy as long as it is sodden in dignity.

So what of the gods? I count four that come to the fore when the wounded Djimenko is brought back to the shrine where other elders remain holed up. We finally get to pick the thoughts of the gods in a surreal sequence as life fades from Djimenko. Sembene’s nuanced touch, one that would run through his later films, has the utmost regard for the customs, but he doesn’t discount the pragmatism Djimenko represents. These are complex times, compounded by the silence of the gods. Djimenko feels his hands were forced by the inaction of the gods.

I also noticed a sense of entitlement as Djimenko appears to almost regard the gods as equals - perhaps the reason he is granted the engagement. You wonder if this sequence with the gods represents another level of consciousness as Djimenko all but chooses the well-being his people over the gods and their demands. In a community that reveres its customs, this comes off as jarring but Sembene is definite in the way he engages us. The dynamic is relatively simple depending one's perspective; for some, certain actions will come off as achieving a level of consciousness and for others, the word may be the dreaded compromise.

-

By: Delali Adogla-Bessa/delalibessa@yahoo.com/Ghana