Ousmane Sembène's Xala

My walk with Senegalese director, Ousmane Sembène continues with his 1975 film Xala, an adaptation of Sembène's 1973 novel of the same name. It’s the most modern of his films I have seen as yet, set some 15 years after Senegal’s independence. After a film like Emitai, where the French occupiers were the subject of Sembene’s scorn, the African elite is firmly in our director’s sights as he exhibits some scathing disdain for upper class who wasted little time in selling out.

My walk with Senegalese director, Ousmane Sembène continues with his 1975 film Xala, an adaptation of Sembène's 1973 novel of the same name. It’s the most modern of his films I have seen as yet, set some 15 years after Senegal’s independence. After a film like Emitai, where the French occupiers were the subject of Sembene’s scorn, the African elite is firmly in our director’s sights as he exhibits some scathing disdain for upper class who wasted little time in selling out.

Xala opens with Senegalese businessmen taking control of the Chamber of Commerce. The men, clad in traditional garb, drive out the French businessmen amidst jubilation and dancing in evoking national liberation. The symbolism proceeds to toe the line of the film’s title, which translates in Wolof to impotence, when one of the French businessmen, a weasely looking man, returns to the chamber with briefcases stacked with le argent. The businessmen, now in western apparel, get that “to hell with nationalism” look in their eyes as they embrace the affliction of impotence fed them by the International Thief Thief.

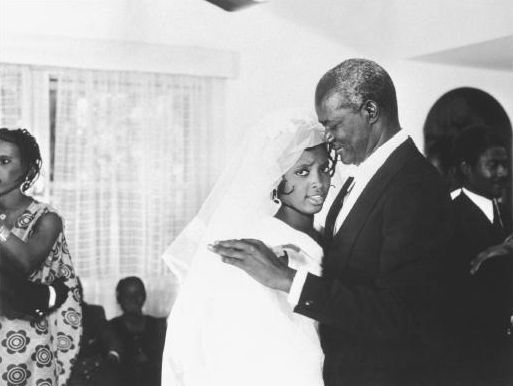

The Xala gets literal when we narrow in on one of the businessmen, El Hadji Abdoukader Beye. He is a picture of excess, corruption and cultural ambivalence. Soon after we meet him, he marries a third wife, young enough to be his daughter, in a lavish garden wedding. When the time comes to consummate the marriage, El Hadji realises he can’t get it up to the irritation of his latest mother-in-law. She had wanted El Hadji to take part in a cultural ritual that tests virility. But aside the fact El Hadji feels his two other wives and kids was proof enough, he thinks he is too good, too modern to be dabbling in such archaic traditional practices.

The irony is El Hadji finds himself at the doorstep of a number of traditional priests in search for a cure for his impotence. Sembène mocks him for this. El Hadji’s warped idea of masculinity puts him in positions that have him dirtying his expensive suits and playing jester in the bedroom to little avail. As to the cause of the impotence, El Hadji suspects one of his wives may have jujued him. El Hadji’s manhood is extremely important to him, so much so that Sembene manages to play on this plot thread to compose one the most viscerally disgusting scenes I’ve seen in cinema since the Matthew McConaughey - Gina Gershon drumstick saga in Killer Joe.

To take a detour from the satire, Sembène’s films continue to intrigue with the nuance and finesse he constructs female characters. On one level, he posits a distinction between women with and without the umbrella of marriage. On El Hadji’s wedding night, his bride’s mother gives her a lecture on her role as wife. Companionship is nowhere the top of the list – remember men and women are not equal. Man is the master. Don’t raise your voice. Be submissive, she is told. The rules, however, don’t seem to apply to women outside marriage as the bride’s mother has no problem bursting into El Hadji’s privacy and roasting him for his impotence.

You question if this is this a reflection of reality or just Sembène’s musings on marriage. There is an interesting parallel with his 2004 film, Moolade, which has a similar dynamic in that, the subject society has edicts that empower women on the one hand, but ultimately leave them at the mercy of their husbands. With the central theme in mind, we see El Hadji try to assert himself over his two eldest wives but they are not as submissive as his third wife’s mother was preaching. His first wife, Adja, comes off as conservative and graceful but never subdued. His second wife, Oumi is western inclined, feisty, and raids El Hadji’s wallet every time he comes by. If anything, she makes him look submissive.

Xala doesn’t miss an opportunity to sneer at El Hadji’s proclivity for excess and corruption on multiple fronts. El Hadji, in Sembene's mind, probably represents the upper class in Senegal, and by extension Sub-Saharan Africa – a stark prophecy of doom. In retrospect, the only thing that has probably changed is, the men go for side chicks instead of more wives. Our director seems to offer a cure, true to his Marxist tendencies – a good old uprising. In hindsight, it is wonderful to note Senegal is one of the few African countries never to experience a coup d'etat.

Sembène is very much regarded as such an accomplished writer meaning he is always working with rich stories to complement his prowess with the language of film. One of the high points sees him paint a picture of the urban business centre with so many moving parts that arrest the senses. It’s the way he passively captures the class divide with the hoard of crippled and leper beggers. We see the traders that contribute to the city stench with their unruly disposal of waste in drains. Amidst this, he purposefully throws in a car crash, working around limitations intelligently whilst an acoustic score provides an air of routine about everything we just witnessed.

But why so serious Ousmane? There are times our director comes off as too blunt; like the scene where he juxtaposes the El Hadji, the corrupt sell out who drinks foreign bottled water, with the businessman's defiant and woke daughter, Rama, who refuses the bottled water like it'll brainwash here. Rama also remains steadfast to the Wolof dialect to the infuriation of her father. Children are the future, they say, and Sembene takes great pride in Rama as slivers of hope for Africa shine through. Cue the heavy handed cut to a shot of Rama with the outline of Africa hovering over her like a halo over the beaming Virgin Mary.

However, Sembene swapped the pen for the camera because he understood the resonance of images like the aforementioned or the final scene of the film which is a Marxist's wet dream. There were reportedly 11 cuts made to the film before its release in Dakar so yeah, it stung in the right places. Xala speaks to the common man but it is sophisticated enough, with its wit and caustic irony, to be held up as a marker of cinema; thoroughly engaging, thoughtful and a reminder of the artistic gold on the continent.

-

By: Delali Adogla-Bessa/delalibessa@yahoo.com/Ghana