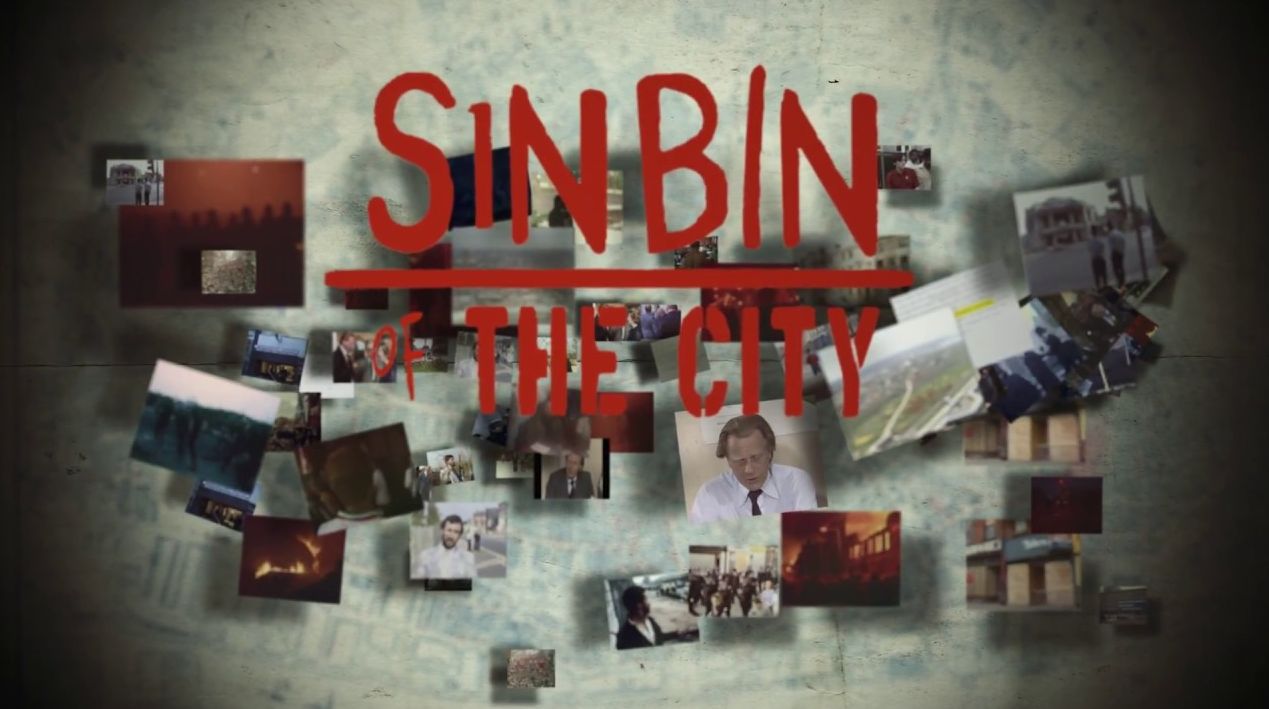

'Sin Bin of the City' review

Watching the 2017 documentary short, ‘Sin Bin of the City’, which reflects on the racially charged 1981 Toxteth Riots in Liverpool, I was struck by was the initial lack of or absence of faces to the voices of the oppressed blacks on the Merseyside. I'm used to the average documentary serving up the standard face-to-face interview as a director looks to interrogate a subject and cut to the crux of a central truth. But our director, James Arthur Armstrong, whilst working with the constraint of keeping his interviewees somewhat anonymous, shows confidence in the voice of his subjects and their laments which are very much relevant to Liverpool and beyond.

Watching the 2017 documentary short, ‘Sin Bin of the City’, which reflects on the racially charged 1981 Toxteth Riots in Liverpool, I was struck by was the initial lack of or absence of faces to the voices of the oppressed blacks on the Merseyside. I'm used to the average documentary serving up the standard face-to-face interview as a director looks to interrogate a subject and cut to the crux of a central truth. But our director, James Arthur Armstrong, whilst working with the constraint of keeping his interviewees somewhat anonymous, shows confidence in the voice of his subjects and their laments which are very much relevant to Liverpool and beyond.

The visuals in ‘Sin Bin of the City’ are comprised of newspaper clippings and news archival footage as well as some smart graphics to aid the narrative. It’s almost like an incredibly engaging presentation in parts. Armstrong makes use of first-hand accounts from black residents of Toxteth as we revisit what the rioting represented - the long-standing tensions between police and the black community. As much as this is a snappy 17-minute history lesson, it is also a portrait of a community, and probably a country, that has made no progress in healing the wounds brought on by racial strife. Racist societies have always left black people in fear of the mundane, so much so that black Merseysiders remember having to walk in groups on shopping trips and the like. The benign-looking Britsh bobbies may not use guns but they were capable of horrid bouts of brutality, as a quick google search will reveal.

Most of my engagement with film content on toxic race relations are restricted to the USA. Earlier in 2017, Katherine Bigelow painted a harrowing picture of if a city on fire in her film about the 1967 Detroit Riots. Documentaries like ‘I am Not your Negro’, ‘OJ: Made in America’ and ‘13th’ give perspective into centuries of evolving racial oppression. Interestingly, Armstrong’s first documentary short was about the uprising in Ferguson, Missouri after Michael Brown was shot and killed by policemen in 2014. Classic Senegalese cinema also shines the spotlight on France and its racist missteps. ‘Sin Bin of the City’ marks the first time I’ve experienced racial tensions in the UK. Every time I’ve seen British police with batons and riot shields advancing on a crowd, it’s been rowdy football fans or striking coal miners at the end of their wrath.

I guess the use of the word “experience” is being accompanied by air quotes because there isn’t much my way of enthralling or visceral footage. There are a few stills of some black men being bundled off to wherever. The shots in the more intense moment seem to favour the police viewpoint but I believe this is a by-product of the somewhat biased news coverage at the time. It’s very clear from ‘Sin Bin of the City’ that we are hearing from voices that have been suppressed for decades. Armstrong’s outlet feels like a hearing before a truth and reconciliation commission, inviting a response from the other side. I would say the court of law, but the ship for justice seems light years away from arriving.

“We’ve been told so many time that things are going to get better. We’ve heard this for so long and we know it’s a lie. Nothing is going to change because nothing has changed. In fact, things have gotten worse over the years.”

Though 'Sin Bin of the City' retains a message of self-worth and hope, this is the saddest line in the film; made sadder by the fact it is unsurprising. It conveys an underlying despair brought on by a racist system that evolved to be less of a hammer and more smarter. Like disenfranchised communities everywhere, there is a lack of social mobility, limited jobs and declining infrastructure. The neglect from the government almost goes without saying. It’s almost like there’s universal playbook for systematic racial oppression.

The Prime Minister at the time, the Iron Lady herself, Margret Thatcher came into power with her right-wing bag of goodies that offered no relief for the neglected black community on Merseyside. Her touting of Victorian values might as well be her saying “make Britain white again”. After the riots, we hear her talk about restoring law and order, which some may know is basically code for “get as many black young men in prison”. The state-sponsored racism only became a little more surgical, with a new and distressing term I learned – "managed decline". Armstrong is trying to start a conversation here. He reminds that wounds have not healed. The quick jump from the 80s to present day at Liverpool community centre lacking diversity is a stark reminder, farcical almost, of the decay.

More time within the community will be needed for an immersive experience to grasp the extent of the neglect within the black community. I really would have liked to have looked into the eyes of some of the interviewees as well as gotten some more personal stories. The recounting of the turmoil is still poignant but more intimacy would have brought something extra to the table and made this feel more empathetic when it sometimes felt academic.

-