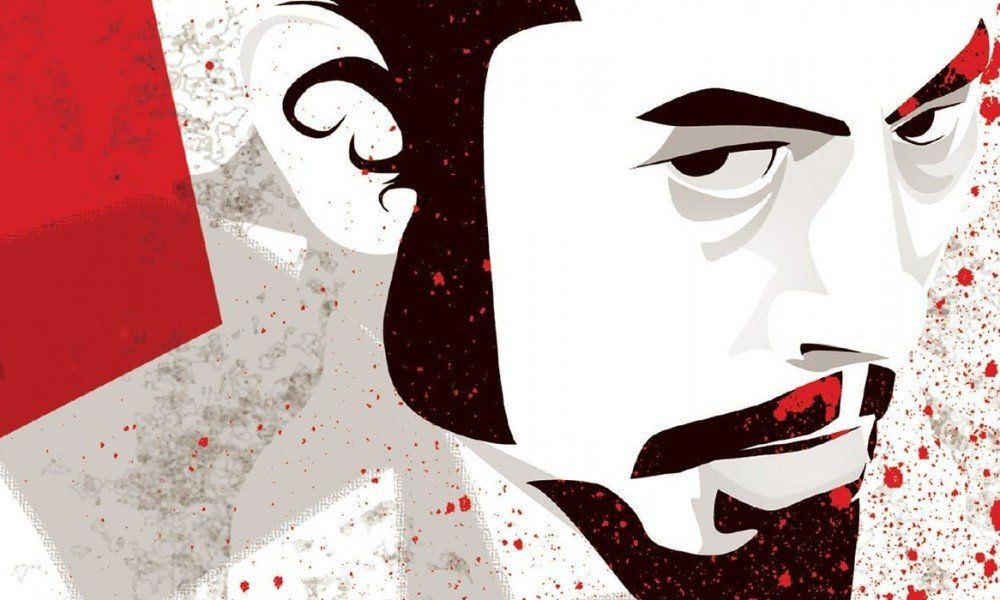

‘Throne of Blood’ (1957) Review

Samurai commanders Washizu (Toshiro Mifune) and Miki (Akira Kubo) lose their way returning home after battle. They encounter an enchantress (Chieko Naniwa) who prophesies great fortunes for them. Fearful and confused, they continue home, secretly full of wonderment.

Samurai commanders Washizu (Toshiro Mifune) and Miki (Akira Kubo) lose their way returning home after battle. They encounter an enchantress (Chieko Naniwa) who prophesies great fortunes for them. Fearful and confused, they continue home, secretly full of wonderment.

Ambition and Murder

When Washizu is made Lord of the North Mansion, which was the first prophecy, he wonders if the final prophecy, to become Lord of Cobweb Castle, will be fulfilled too. Meanwhile, wife Asaji, (Isuzu Yamada) is metaphorically rubbing her hands with glee at the prospect of becoming Lady of Cobweb Castle and is keen to expedite her husband’s succession to the throne.

“Without ambition a man is not a man,” she goads him, as persuasion to murder his friend and comrade, the current Lord of Cobweb Castle.

“That is high treason,” he argues, shocked at her brutal suggestion.

And thus begins the seemingly unstoppable chain of events tarnished with the blood of many.

Stylised

This stylised version of Macbeth, set in feudal Japan, far away from the Scottish highlands, is regarded by some to be the best working of the Scottish play yet and director Akira Kurosawa’s finest hour. Strong influences by Japanese Noh drama give the production a sense of theatre, perfect for the supernatural element and a vehicle for tension in a piece that was written for the stage. Shot mostly on Mount Fuji, the interminable fog is real and does justice to Shakespeare’s grim tale of evil, greed and madness.

Turmoil and Madness

Mifune does not present Washizu (Macbeth equivalent) as an evil madman. He is a trained warrior and seems in a permanent state of confusion. One imagines that his life before the prophecies was a simple one, albeit a tough one and his manic expression throughout is indicative of the turmoil in which he finds himself at the hands of the supernatural and his domineering wife. Yamada does not bring the usual Lady Macbeth passion to the part of her equivalent, Asaji. In keeping with the Noh style, every movement is choreographed and not one is wasted. She glides like a ghost; maybe to hint at things to come or maybe to imply she has powers that are beyond human. She moves from detached coldness, to wide-eyed fear and ultimately, detached madness. Credit to makeup artist Masanori Kobayashi for her geisha type mask, giving her a sinister look and symbolic of her changing personality.

Beauty

Instead of three witches, we have just one forest spirit, appearing initially in a white bamboo structure resembling a birdcage. Unlike most interpretations, there is a spellbinding beauty to the manifestation. With non-Shakespearean language, there is more licence to deviate on occasion from the play, which portrays the witches as so ugly that their gender is questioned.

Japanese Shakespeare

So easily does the story lend itself to Japanese culture, that it could pass for Far Eastern mythology. We are accustomed to modern Shakespeare, surreal Shakespeare, traditional Shakespeare … but here is a rare opportunity to see Shakespeare in an entirely different culture and it is a resounding success.