Truffautbruary, a month dedicated to Francois Truffaut: Day for Night

Francois Truffaut wrote the greatest, most beautiful love letter to the cinema with his 1973 film, Day for Night.

Francois Truffaut wrote the greatest, most beautiful love letter to the cinema with his 1973 film, Day for Night.

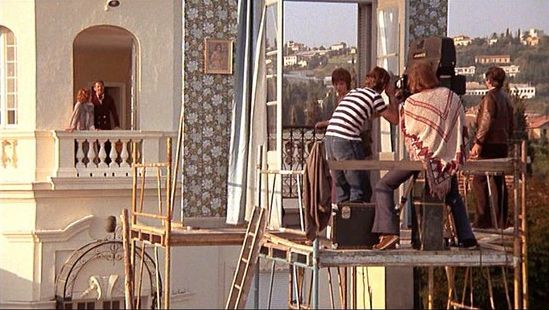

Intrigued by the remains of a huge abandoned film set complete with several building facades, a subway entrance, and a Paris sidewalk cafe, the idea presented itself to Francois Truffaut to make a film about the creation of a movie. This intrigue fulfilled a lifelong wish of Truffaut's to film about the inside workings of the demands on a filmmaker, and what it's like to make a film. Truffaut called this venture "a profession of faith in cinema" and "a true and sincere film on an artificial world." Much to my delight, Truffaut would appear in this film as the director of a film he is making, though the character is not intended to be a version of Truffaut as a filmmaker. The intention was to provide a neutral, professional image of the working film director, rather than a direct interpretation of himself as an artist. Day for Night is still a Truffaut film, however, and many autobiographical elements exist. Deciding to approach the film with a graphic overview of what the film would be, yet leaving enough room to deviate, Truffaut was confident that his small crew and 42-day shooting schedule would bring his love letter to the cinema to the screen. At the time of its production, Day for Night was the project closest to Truffaut's heart, as he would say, "The subject of Day for Night was, quite simply, my own reason for living." Premiering on May 24th, 1973, Day for Night would bring Francois immense critical praise and become his most internationally celebrated film.

French filmmaker Ferrand (Francois Truffaut) is completely devoted to the cinema. Believing movies are the most important aspect of life, he reserves his most reverent feelings for movies and their creation. He is completely consumed by thoughts of the cinema, even when he is not working on his latest film, "Meet Pamela". Ferrand loves the world of movies even if a movie set is not the easiest or most relaxing place to be. During his own shoot, he has to worry about his lead actress, Julie Baker (Jacqueline Bisset) and her recent struggle after suffering a nervous breakdown, his immature lead actor, Alphonse (Jean-Pierre Léaud) who is more interested in what his girlfriend the script girl is up to rather than his performance in the film, Séverine (Valentina Cortese) an aging actress fearing her best days are behind her who has turned to drinking on the set, working around the surprise pregnancy of one of his principals, the production manager whose wife has taken to following him around on set, and how to deal with promoting a film after one of the actors has died during its production. Ferrand's hands are full, to say the least, but he still seems energetic and completely devoted to the film he is making despite the numerous issues he encounters. Truffaut masterfully displays all of the problems that arise while working with a great number of people and the technical issues that occur when trying to bring your dream to cinematic reality. What Truffaut also shows are the personal developments and everyday lives of those starring in and working on a movie. Day for Night is a magically multi-dimensional film, bringing together every aspect that goes into film production with his trademark humanism that also captures the lives of those involved in filmmaking.

"Meet Pamela", the film within the film about film, treads familiar ground for Truffaut and is one I wish I had the opportunity to see. In the film he is creating, Ferrand shows a newly wedded couple (Jacqueline Bisset) and (Jean-Pierre Léaud) meeting the parents of the husband for the first time. When his new wife meets his father, however, Bisset's character falls in love with him, and he with her. Lust and betrayal are the themes of the film when the triangular love emerges. The production problems encountered mirror the upheaval taking place on the set of the movie they are making as lives are forever altered by what they experience and what is happening around them. The best part of Meet Pamela is that Truffaut incorporates much of what inspired him to make Day for Night in the first place, highlighting the one-sided film sets, the movie-making tricks and the cinematic sleight-of-hand that goes into film production.

Perhaps the best part of Day for Night is the dream Ferrand keeps having when he is finally able to rest after a day's work on the film set. Each night, Ferrand gets a little bit further in his dream, culminating in the most charming ode to the cinema I have ever seen. On the first night of Ferrand's dream, we see a young boy running under the cover of night in a deserted street, nervously looking back at the path he has just traversed. On the second night of his dream, we see the same boy running and looking over his shoulder, but we see him make it to the destination he was running towards, a locked gate. On the final night of his dream, the same scene unfolds until finally, the boy is kneeling at the gate in a perfectly reverent manner when it is revealed to the audience that beyond the gate are a collection of one-sheets featuring Orson Welles and Citizen Kane. After some difficulty, the boy begins untacking the pictures and putting them in a pile that he takes with him before running away. Not only is this depiction of theft one of the most endearing I have ever seen, it is also autobiographical of Truffaut's own childhood. As a boy, Truffaut and his best friend Robert Lachenay would steal the movie postings and type them up in a periodical, of sorts, and sell it as a means for the young boys to make some money. Even as a child, Truffaut's devotion to the cinema is certainly something to marvel at, as he was forever devoted to making cinema an active part of his life. The dream sequence Ferrand experienced had its own unique tone and style setting itself apart from the rest of the film in gorgeous black and white photography. The dream is akin to a symphony, as it passes through three distinct movements. First, we see the pressure the boy endures as he nervously looks around to make sure he's not being watched. We see the fear creep up on the boy's face yet he remains determined and committed to his task. We then see the look of determination as the boy mentally plans his journey, though still obstructed by the gate with the audience unaware of what's on the other side. The final and most powerful movement of the symphony of Ferrand's dream shows passion emitting from the boy when he can finally touch the posters he has been seeking all along. This desperate need for cinema illustrated through this elaborate scheme to steal the artwork from a film, display a passion for cinema that Truffaut himself was known to possess. This dream sequence may be the most powerful bit of autobiographical realism in Truffaut's career, but certainly since his debut, The 400 Blows. The dream is so incredible to watch because it captures the unique way in which cinema can be a truly life-saving commitment.

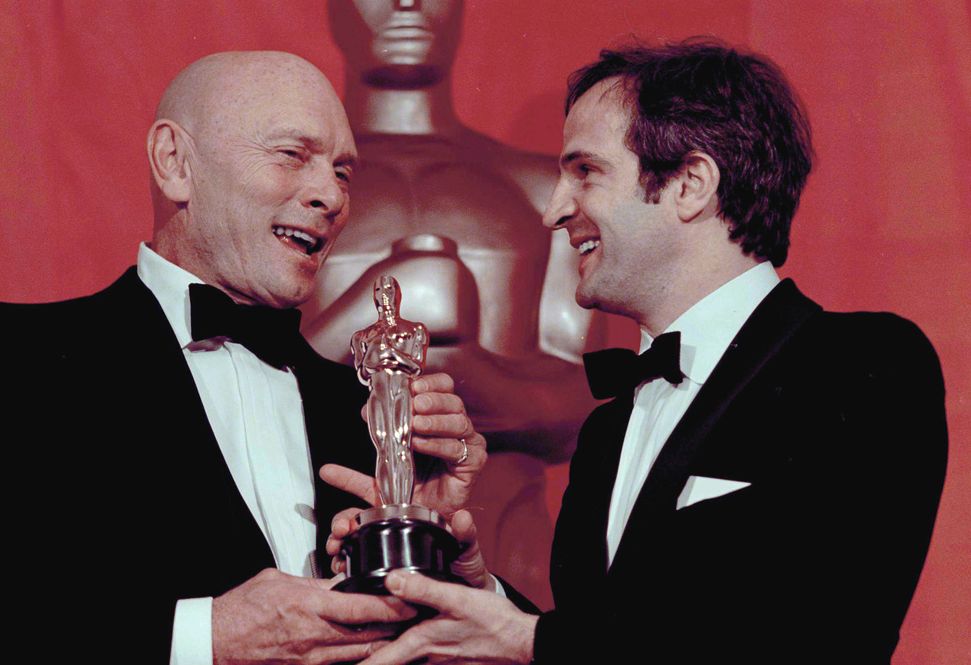

Day for Night was a massive critical and commercial success bringing Truffaut his first and only Oscar for Best Foreign Film. Upon winning the award, Francois addressed the Academy and all in attendance succinctly by saying: "Merci beaucoup. I need Gene Kelly. I am very happy because... because why? Because "Day for Night" is a film about show people. You are, all of you, movie people. Because [of] that I think this prize is yours. But if you agree with me I will keep it for you, alright? Thank you." Forever embarrassed by his struggles of learning English, Truffaut referenced Gene Kelly in his speech as he had earlier in the celebration translated the acceptance speech of the French-speaking Henri Langlois. The speech sounded graceful, and the sentiment was even more lovely, with the entire room seeming to celebrate with Truffaut the fruits of his film, Day for Night. Truffaut was deeply pleased with the film, and the almost universal praise he received did much to bolster his confidence, though the most surprising bit of fallout he endured was the end to friendship and counterpart.

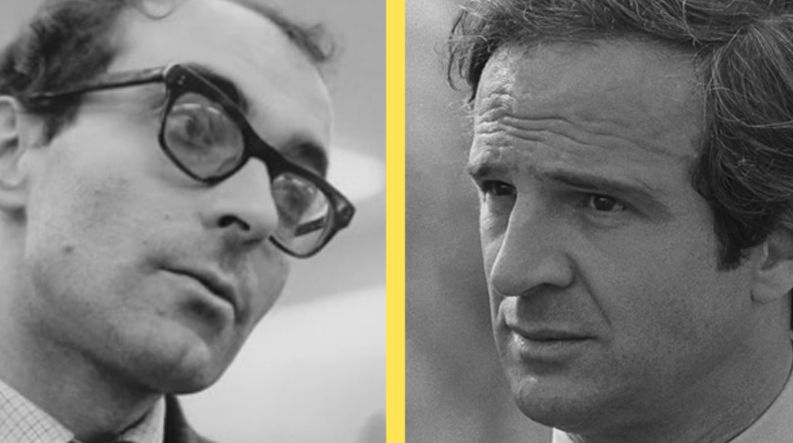

Day for Night had enjoyed such praise it was difficult to imagine that its harshest critic would come from a source closest to Truffaut. jean-luc godard would write a scathing letter to Truffaut after he walked out of a screening of the film in disgust. godard was completely disgusted with the way Truffaut portrayed filmmaking in Day for Night criticizing him for being an apologist and missing all of the profound questions of filmmaking through his illustration of a film set. Attacking the moral and ideological compass Truffaut used to make the film, godard accused Truffaut of goading audiences, using vast sums of money, into falsely believing that there is a magic in movie making when the reality (to godard) is that movie making is all about power. Early in the letter, godard writes "Yesterday, I saw Day for Night. Probably no one else will call you a liar, so I will." In addition to seeing Truffaut as a filmmaker who presents filmmaking in a disingenuous manner, godard, in the same letter, asks Truffaut for money to diversify his filmography and to come back to the smaller budget films of his roots. Sickened by the fact that he made such a big budget film that was so well-received by international audiences, godard thought of it as an obligation of Truffaut's to donate money to godard's next project. Truffaut and godard were old and dear friends, both coming to the French New Wave at the same time, even co-directing a film together. Truffaut was essential to godard's career getting started, as it was Truffaut that wrote the original screenplay before giving it to godard to direct while he made The 400 Blows. To say that this letter he received from godard felt like a betrayal would probably be an understatement, so when Truffaut responded, he did not hold back, writing "Jean-Luc. In order to for you not to be obliged to read this unpleasant letter until the end, I shall begin by the essential: I shall not co-produce your movie." he then goes on to say." Truffaut then goes on to defend the various people godard unleashed attacks towards in his previous letter and to famously say that [for years] godard had been acting "like a shit." My personal favorite quip from the correspondence is where Truffaut writes: "You should by no means hastily throw together the preproduction work on your next autobiographical film, whose title I think I know. Once a shit, always a shit." Truffaut's sass game was strong, and godard had desperately underestimated his friend when he wrote to him, as the two would never speak again, something godard deeply regretted. godard should regret both his behavior and his letter, as what he really displayed was a fundamental disagreement about the power of cinema and the heart of moviemaking rather than a monopoly on the truth. Cinema did save Truffaut, and he was enamored with the magic of a crowded movie theatre. Truffaut put himself and his passion onscreen for audiences to see rather than forcing a political or ideological viewpoint the way godard did. Neither technique to movie making is fundamentally wrong, they are simply different sides of the same cinematic coin. The bottom line is that Truffaut is one of the most humanistic filmmakers I have ever experienced, his pulse runs through his films and then runs through the audience that watches them. Almost as a means of defiance against his loveless childhood, Truffaut grew into a loving person who sought to deliver magic on the screen everytime he undertook a project. godard made movies he wanted to make, which is admirable, though he did not care who he alienated, which is not. A person well-known to be difficult, godard seems to color all of his characters with a certain level of disdain informed by what I can only imagine is a negative interpretation of the human race. I suppose it makes sense, knowing what I know about godard and his films, that he would have been sickened by all of Truffaut's films, though especially Day for Night because it presents a world where people have passions and love each other, a concept that would have been foreign to godard.

Any serious fan of cinema will be absorbed by Francois Truffaut's Day for Night from the very beginning of the film, as it captures the vibrancy of a film set that many of us will never experience first-hand. There is an air to the film, part of which I cannot describe that instantly communicates that you are watching a love story, though it is not a love story between two people, but rather, between a man and the cinema. Watching Day for Night is as close to magic as one can get. Film isn't painted with a broad stroke of perfection, but rather, its imperfections are exposed only to make cinema as a whole more loveable. No matter how many times I see Day for Night, I can never watch it all the way through without crying over seeing Truffaut himself onscreen. I feel especially warm anytime I get to watch Truffaut acting in one of his films, but to see him onscreen in Day for Night is especially profound because I know how much of a passion project it was for him. It is also a sincere joy to see him acting alongside Jean-Pierre Leaud, both with such energy, charm, and charisma, knowing that it was Truffaut that brought Leaud to the screen as a means to communicate himself with the world. Truffaut's films are so personal and heartfelt it is nearly impossible not to be moved by what he illustrates. There is a collection of scenes where Truffaut, as director Ferrand, is taking great pains to communicate to his actors exactly how they should stand and carry their bodies while shooting a scene that doesn't come off as needless perfectionism, but rather as a beautiful bit of visual poetry. This visual poetry defines all of Truffaut's films but perhaps is never more apparent than it is on Day for Night. There is a bit of the film that highlights how a film set becomes like a family, and one gets a sense that Truffaut truly believes this. It makes sense that Truffaut would share a kinship with anyone involved in making movies, but especially those involved in the production of his own movies. The exceptional music, the lively editing, and the autobiographical elements in Day for Night create a stunning package of movie allure. Truffaut recycles an event that happened to him when he was shooting The Soft Skin. A stray cat had begun wondering the set and drank out of a saucer on a serving tray while filming a scene. Truffaut was so moved by this organic, often overlooked difficulty in filming that he incorporated it into a lovely comedic scene in Day for Night. Truffaut's commitment to himself as an artist and telling the stories that he knew in his heart has endeared him to the hearts of cinephiles throughout the generations.

Francois Truffaut exhibited an interesting relationship with death in his cinema. Acutely aware of mortality, especially when those that he had worked in films of his began to die, Truffaut never shied away from exploring death through his films. In The Bride Wore Black, Truffaut addresses both suicide and murder, in The Green Room, Truffaut chronicles the relationship one man has with the dead, erecting shrines of those passed on in his home as a means to honor them. Several other examples exist throughout Truffaut's filmography that suggests death was something he thought of, often. Dealing with death again in Day for Night, Truffaut presents a fascinating symbolism. One of the actors in "Meet Pamela" dies during the production of the film, leaving the cast and crew both heartbroken and unsure of how to finish the film without him. Director Ferrand finds a way, and the film is finished, but immediately after he is questioned almost solely about the actor's death and what that meant for the film and for cinema. The death of big-name actors and the wave of new, young talent seems to represent the death of a previous way of making movies and a new way that is being ushered in. Much like Truffaut was part of a new way of looking at cinema and what it represents, and brought with him a unique voice that had not yet been heard, there was another wave behind him. The only constant in life is change, and in filmmaking especially, there is no time to get comfortable in being at the top because there is always someone else vying for that position behind you. Day for Night then acts as a reverential homage to the cinema of the past, and a welcoming embrace for the cinema of the future; and really, what more could you expect from someone who simultaneously soaked up all of the classic cinema he could yet benefited so greatly from breaking tradition.