Truffautbruary, a month dedicated to Francois Truffaut: Love on the Run

Seeking a sure-fire money maker after a commercial failure, Francois Truffaut reunited with his mascot, Antoine Doinel to help him move past some of the recent negativity he had experienced in his career.

Seeking a sure-fire money maker after a commercial failure, Francois Truffaut reunited with his mascot, Antoine Doinel to help him move past some of the recent negativity he had experienced in his career.

Banking on a fast shoot, only a 28-day filming schedule, Francois Truffaut imagined that a final collaboration with Jean-Pierre Léaud, as his character Antoine Doinel, would perfectly illustrate the "mosaic of life." Truffaut went into Love on the Run needing to make money for his production company after suffering a financial loss with his much later appreciated masterpiece, The Green Room. There were a number of other projects dear to Truffaut's heart that he had wanted to pursue at the time, but as a means to save his company, he put his energy into a previously unplanned Antoine Doinel finale. Truffaut was never happy with the script of Love on the Run, hating it from its earliest conception. Despite his attempts to pivot his energy, he was not happy with being in the situation, feeling forced to take the project on. Love on the Run was a commercial success, but Truffaut was never happy with it. Still, Truffaut was emotionally connected to Antoine Doinel and saddened to say goodbye to the character that launched his career.

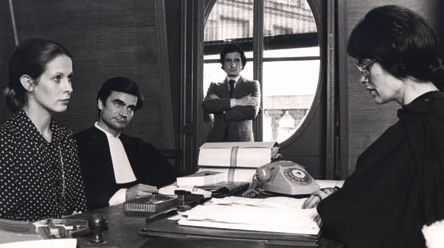

After five years of separation and reconciliation, Antoine (Jean-Pierre Léaud) and Christine (Claude Jade) have finally decided to divorce. They have reached the decision amicably, and are committed to maintaining a healthy relationship post-divorce. Upon leaving the courtroom, Antoine is seen by his former flame, Colette, (Marie-France Pisier) who now works as a lawyer. Intrigued by her chance glance at Antoine, Colette picks up a copy of his autobiography interested to see what has become of the young man that so desperately chased her heart years before. Antoine has been having a casual relationship with a record store clerk, Sabine Barnerias (Dorothée) contemplating whether or not to become more serious in his intentions with her. Sabine, deeply in love and committed to Antoine was put off by his neutral stance in their relationship and informs him that she may be interested in dating other people. Never one to appreciate being backed into a corner, Antoine leaves Sabine's in an unhappy hurry to pick up his son. While taking Alphonse to the train station to send him off for the summer, Antoine sees Colette and jumps onto the platform eager to be reunited with her. The two have a nice time reminiscing about their adolescent love and telling each other about the relationships they have had since they last saw each other. Finding himself in another dilemma in love, Antoine must decide between pursuing a relationship with one of the women, or remaining alone and focusing on career and fatherhood.

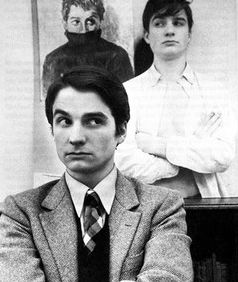

The Adventures of Antoine Doinel, the five-film collection depicting a version of Truffaut, was written by him and inspired by events in his life, making them a personal and deeply affecting anthology. Truffaut's willingness to inject so much of himself into each of his films, but especially those in the Antoine Doinel series, make them endlessly thought-provoking. Driven by Truffaut and his life, the films communicate so well with audiences, in no small part, thanks to the expert casting of Jean-Pierre Léaud. His playful yet searching disposition lent itself well to the perpetually unsatisfied Antoine Doinel. The part of Antoine needed to be brought to life by someone who could embody a boyish charm with immeasurable charisma, and Truffaut found exactly that combination in Jean-Pierre Léaud. Along with the exceptional casting, Truffaut's particular film style created an engaging an extraordinarily fun time with the character closest to his heart. Love on the Run is filled with flashbacks reminding the audience of Antoine's progression and highlighting the ups and downs with the loves of his life. The intercutting of Truffaut's previous films in the series was a brilliant device to use for an anthology wherein many years passed between one film and the next. Many have criticised Love on the Run due to its reliance on flashbacks, but I can't imagine a better way to understand Antoine's growth and development as a person. Seeing the scenes from his troubled relationship with love and his searching for a family and acceptance allows the audience to best understand Antoine as a person. I suppose ones ultimate opinion on Love on the Run will likely depend on how you feel about the number of flashbacks used in the film, for me, they work perfectly and Truffaut works them in perfectly. Not a single scene feels out of place or unnecessary, again proving Truffaut's exceptional intuition as a filmmaker. Even in 1979, long after Truffaut was first accused of abandoning the movement he ushered in and giving up on doing anything different within the medium of cinema, he affirmed he was not done taking chances. His confidence boosted by talking to Colette, Antoine shares with her the premise of his next book, a novel that was inspired by an episode he witnessed while waiting outside of a phone booth. The scene takes place with Antoine and Colette on the train and shows him reminiscing about the incident he saw wherein an angry man ripped apart a photo while yelling at someone on the phone. As Antoine tells the story, the version of himself in the flashback suddenly becomes cognizant that he is in a flashback, and he addresses the camera by brilliantly breaking the fourth wall. The scene is playful, in line with Antoine's character, and done in an experimental way to engage the audience and show that Truffaut had not strayed from his early intentions in filmmaking. That phone booth scene is such a perfectly quirky scene it is my favorite in an already stellar feature.

Forever the humanist, Francois Truffaut beautifully explored love and what it's like to finally accept the end of once-nurtured devotion. Complicated mixed feelings emerge anytime people go through a divorce, especially when they have put so many years into a hopeful reconciliation. Antoine and Christine share a child together and the memories of their life together before their son were born and their elation at bringing him into the world plays into their emotional state, as well. Truffaut takes us, using flashbacks, through the depths of their most committed love, the pain and heartbreak of betrayal, and their eventual decision to leave each other. Just as in Ingmar Bergman's Scenes from a Marriage, Antoine and Christine can't stay hateful or bitter to the other, despite the unfaithfulness that took place. It is clear that the couple has a genuine love for each other that will not be distinguished by divorce. They have a palpable affection, and will always be invested in the best interest of the other. In addition to his humanism, another aspect of Francois Truffaut's filmmaking that I appreciate are the autobiographical elements in each of his films. There is a moment where Antoine confesses that many don't think of him as a true writer because he has only written about experiences from his own life. He goes on to admit that he has faced criticism that suggests he is only capable of drawing from personal experiences in a transparent and conscious way. This seems to be Truffaut addressing those that had attacked him in a similar way for the personal elements found in his own art. Much to the contrary, however, those that so freely open the personal wounds from their own life to the criticisms of the masses are connected to their art in a much deeper way because it is in the truest sense a part of them. Truffaut's commitment to the cinema cannot be questioned and his personal approach in developing a relationship with filmmaking only gives his films a deeper resonance. It's impossible to tire of the individual films provided by Francois Truffaut, I only regret that there are not more to see.